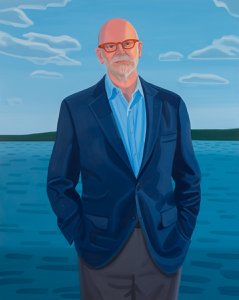

Barry Mills: Opening of the College, Convocation 2013

Bowdoin College’s 212th Convocation was held Wednesday, September 4, 2013, in Pickard Theater, Memorial Hall. Following is the text of President Barry Mills’ “Opening of the College” address.

Good afternoon, everyone. It is my honor to preside at the official opening of the 212th academic year of Bowdoin College.

Today, I am very pleased to welcome our faculty, staff, students, and friends to this traditional ceremony, and to offer a particular welcome to the members of the Class of 2017. I am delighted that so many members of our impressive first-year class have come to celebrate with us. During the past couple of days, I have had the opportunity to greet and chat briefly with each and every member of the class, and to watch you join the generations of students before you who have begun their Bowdoin careers by signing our Matriculation Book. I can confidently say to our faculty and staff that the Class of 2017 is able, enthusiastic, and serious, and that its members are clearly ready for all that Bowdoin has to offer. I know they will make important and lasting contributions to the College over the next four years and beyond.

It is my practice to focus my remarks at Convocation — as well as those delivered during Baccalaureate in the spring — on issues and ideas of importance to the College. In the past, I have used this forum to discuss the centrality of the arts in the liberal arts, academic freedom, sustainability, the fundamental importance of financial aid, issues of race and socioeconomic class, the role of technology in education, and a number of other issues.

Today, as we begin this new academic year, it is important for us to acknowledge that now — more than in any time in our recent history — the purpose, value, and utility of a college education are being analyzed by our national leaders, the news media, and by families across America.

We are a nation conflicted about the purpose of higher education. In some respect, I believe this confusion is driven by the many goals we set for our educational institutions. The relative importance of these assorted goals is distinctly affected by the economic conditions of our country and the political environment. And the situation is made more complicated by the variety of educational institutions in America and the failure to distinguish among them in our national discourse.

For many, college is a place where students simply go to spend four years to grow and mature from adolescence to adulthood. A time well spent in a four-year residential college is thought of as a relatively safe right of passage for young people, as they prepare to live their lives as independent citizens. But quite appropriately — given the high cost of college and the debt burden assumed by many students — this traditional right of passage seems to many to be a luxury that our country must reconsider.

College is also seen as a vehicle for our young people to gain the skills and information for employment, or to prepare themselves for graduate or professional school. Here again, given the high cost of the education and the burden of debt, there are legitimate questions about the efficiency of the model and the ability of some institutions in higher education to achieve these goals.

The transformational changes in education presented by technology have also created a new conversation about our educational systems. I spoke last year about the power of technology and modes of education, and how there is opportunity even for a college like Bowdoin to be a better place using educational technology in thoughtful and imaginative ways consistent with our mode of liberal arts education on a very personal basis. There is widespread hope that technology will flatten access to education across the socioeconomic spectrum in our country and the world. And, there is also hope that technology will bend the cost curve of education making education not only more accessible, but also more affordable.

Throughout our history, colleges and universities have been seen as institutions that serve society as centers of research and innovation. This role and responsibility is certainly consistent with the intellectual and professional motivations and aspirations of our faculty for research and scholarship, and our educational institutions have always eagerly taken on this work with substantial federal support and with some state investment. But here again, as federal funding is reduced and state budgets are slashed, there are serious questions about the efficacy of this traditional role for higher education.

Here at Bowdoin — and at other colleges and universities dedicated to liberal education — we seek to educate students broadly in the sciences, the humanities, social sciences, and in our interdisciplinary programs, as we also work to instill a passion for lifelong learning. At Bowdoin, our guidepost is The Offer of the College. Another formulation, by Thomas Jefferson, put it this way:

“The objects of education are to give to every citizen the information he needs for the transaction of his own business; To enable him to calculate for himself, and to express and preserve his ideas, his contracts and accounts, in writing; To improve by reading, his morals and faculties; to understand his duties to his neighbors and country, and to discharge with competence the functions confided to him by either; To know his rights. And, in general, to observe with intelligence and faithfulness all the social relations under which he shall be placed.” ¹

Simply put, it is the mission of colleges and universities to educate students to become engaged, thoughtful, principled citizens who understand the complexities of life and who are prepared to become leaders in all walks of life. And yet today, this mission is frequently dismissed, largely because our country is divided politically and because of the huge costs associated with these “less-than-consumer-oriented” goals.

Other doubts are coming from within the academy itself. I encourage you to read “The Heart of the Matter: The Humanities and Social Sciences for a Vibrant, Competitive and Secure Nation,” prepared by the American Academy of Arts & Sciences. This report makes a forceful and important case for the humanities and the social sciences, while also acknowledging the sciences. But, sadly, the report also seems to have been prepared in an atmosphere where some associated with these fields are questioning both the value of these disciplines and their own self-worth.

In recent weeks, while this atmosphere of doubt and reevaluation has been percolating, President Obama appropriately and correctly focused the attention of the nation on the efficacy and affordability of higher education. The President points out the clear connection between a college education and a good job—the direct relation between income and college achievement. He also speaks about the crushing debt students take on to pay for that education and the dramatic failure of students to graduate from colleges where they enroll (problems that most Bowdoin students do not face, on either account). The President proposes that we “rank” our college and universities to make more transparent graduation rates, debt burdens, and access to college for students with low and moderate incomes. He talks about rewarding colleges and universities that use technology in innovative ways to educate students more broadly and efficiently. Surely, graduation rates, debt burdens, access, and efficiency are all important factors when considering college, and we have read that many college leaders approve of this new focus by the Obama Administration, even as they remain wary of the rankings themselves. These leaders appropriately worry about a “one-size-fits-all” ranking system.

Well, all colleges hate rankings, unless of course they are ranked very high (like Bowdoin food, or our science labs, among many other high rankings). But, more substantively, I think the skeptical reaction to the ranking concept is a reaction to the President’s message that college is about job preparation first and foremost. This is a natural focus at a time when the middle class is being squeezed and the lower class is being left behind, and at a time when the education is incredibly expensive and the debt burden so high. While our leaders are concerned about creating educated citizens, these days, it makes good sense that their focus should be on preparation of our students to be employed.

Colleges and universities have been working for years to ward off this consumer culture and perspective, at least in terms of their self-perception. But, of course, the “arms race” of academic programs, sports, and new buildings only contributes to the consumer culture.

What does all this mean for Bowdoin? What is our role as educators and students and staff on these issues?

At the very least I think it is important for us all to be engaged in these national issues and not feel we are insulated by the strength and security provided by Bowdoin.

Also, more than ever, it means that as students certainly — but especially as faculty and staff — we must work diligently to be excellent individually and as a college. We must redouble our efforts to be ambitious individuals and an outstanding institution preparing our students for a life of the mind and lifelong learning. And, we must be prepared to do this work in an environment of more limited resources where costs continue to escalate and our ability to pass these costs on to our students and their families must be kept under control.

Anyone sitting here who has a student in college or young children at home, must be asking themselves the same question many of our young alumni ask me: “How can it cost so much to go to Bowdoin and how will we ever be able to afford it?”

It’s true that people have been asking similar questions for generations. But with humility, I believe these times are different, and at least for a while, given our economic conditions and relatively long-term wage stagnation in the United States, there are genuine limits on what we can charge.

You will read soon, and I can announce today, that for the first time in our history, the endowment of Bowdoin College exceeds $1 billion. This is a phenomenal accomplishment for our College, especially given where the endowment stood just twenty years ago. This endowment growth is due to the enormous generosity of our alumni, parents, and friends. It is also due to the prudent and brilliant management of our endowment by our Senior Vice President for Investments, Paula Volent, and an investment committee that is thoughtful, nimble, and disciplined.

Bowdoin is strong financially, but we must continue to be disciplined. The vast costs of operating this College are not driven by excellent food or new facilities, as some simplistic analysis suggests. It isn’t because we have a climbing wall in Buck or new landscaping around the Moulton Union.

Our costs are driven by the many, many programs of this College — a.k.a., people. They are driven by the research we do, the support our students and faculty demand from staff, our athletic programs, and the ever increasing and seemingly insatiable demands for obtaining and maintaining technology, which in many respects has become the equivalent of the “steam pipes” of the College, but a whole lot more expensive.

Since these ever increasing costs are not matched by an ability to charge parents and families additional fees, we must rely more and more on the endowment to meet our expenses. Have no doubt, Bowdoin is in a good place financially, but only if we continue to be disciplined and thoughtful in how we operate the College in the broadest sense. This means that with every new idea and with every existing program we are careful to evaluate the effectiveness of that program in the context of whether it is well designed, ambitious, and excellent and with a careful eye on the cost of college to our families. Our College simply will not be sustainable in the long term if the program we deliver is not affordable to the middle class of America. It must be affordable to the middle class of America.

This affordability is linked inextricably today to our endowment. Today, nearly 45% of our endowment is restricted to be spent on financial aid, and nearly 30% of our endowment is restricted to be spent on our academic program, libraries, and museums. Our endowment must continue to grow through prudent investing designed to maximize our returns, but we must not assume outsized returns into the future, given the economic conditions. And, the endowment must continue to grow through the continued substantial support of alumni, parents and friends. How do we all generate that support? Very simply, we will generate this support and commitment by each of us being excellent individually and excellent as an institution.

This excellence is measured in many ways. It is measured by our ability to promote learning that allows students to grow intellectually and mature as people who love this college but who are also challenged by it.

There is the excellence of the scholarship, research, and artistic work of our faculty.

There is also the excellence evidenced by the recognition our faculty receive — recognition from their peers in the academy, and also from inspired students and alumni.

There is excellence evidenced by the jobs, fellowships, graduate and professional degrees our students achieve after Bowdoin.

There is excellence represented by the strong sense of who we are and by our adherence to the long-held values of this College, including what I am confident is our well-defined sense of the common good.

And, there is the excellence represented by our graduates who go off from Bowdoin to become respected and responsible citizens — citizens of the United States and citizens of the world — principled leaders in all walks of life.

We live and learn today in a world that appropriately questions the value of what we do at Bowdoin College. But we know — and our alumni, parents, friends, faculty, students, and staff know — that what we do is special, significant, and central to the intellectual and ethical strength of our nation and the citizenry of our communities. Our mission and our challenge are to continue to do what we do with an uncompromising focus on excellence, quality, effectiveness and the values embodied in the common good.

I now declare the College to be in session. May it be a year of peace, health, success, and inspiration for us all, and a recommitment to our most important tradition: teaching and learning together. Thank you.

¹ Thomas Jefferson, from “Report of the Commissioners for the University of Virginia,” August 4, 1818 as referenced in the American Academy of Arts & Sciences report “The Heart of the Matter,” 2013