Two Centuries Later, Bowdoin's Longfellow-Dante Connection Lives On

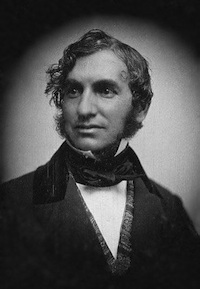

By Bowdoin NewsAmong the many claims to fame of Bowdoin’s luminary alumnus Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Class of 1825, was his distinction as the first American translator of Dante’s The Divine Comedy in its entirety.

Longfellow venerated Dante, referring to him in a lecture at Harvard as “Lord of the most high song, who like an eagle soars above the others.”

Dante’s place in the pantheon of great poets wasn’t always secure on this side of the Atlantic, where Greek, Latin and French ruled and Catholic authors were only grudgingly given entrance into the academy.

Longfellow was key in establishing Dante’s renown in America. He introduced students to his works while teaching modern languages at Harvard and in 1881 founded the Dante Society of America (DSA), one of the oldest literary societies in the U.S.

The most recent issue of the DSA’s journal, Dante Studies (Vol. 128, 2010) is devoted to this Longfellow-Dante connection. The special issue includes twelve scholarly essays, two early documents, and a short story by Matthew Pearl, picking up where The Dante Club left off.

It also features two works by recent Bowdoin alumae who got fired up by The Divine Comedy while studying at Bowdoin with Associate Professor of Romance Languages Arielle Saiber — who co-edited the volume with Yale's Sterling Professor of Italian Giuseppe Mazzotta.

In “The Seed of the Stately Tree: Longfellow and Dante at Bowdoin College,” Kelsey Abbruzzese ’07 uncovers new evidence of Longfellow’s encounters with Dante as a student and then during his years as Bowdoin’s first professor of modern languages.

Longfellow’s famous translation of The Divine Comedy began at Harvard, as is wickedly reimagined in bestselling author Matthew Pearl’s mystery novel, The Dante Club. However, his trailblazing quest to introduce Dante into the classroom began much earlier.

Such a distinction may at first seem pedantic, but Abbruzzese’s research reveals a seminal time in Longfellow’s early career that is often eclipsed by his later accomplishments as poet and professor.

“Once he began teaching [at Bowdoin], his love of languages – especially Italian – became apparent to both faculty and students,” she writes. “Dante soon came to be a major part of his academic life.”

Abbruzzese was able to access primary documents in Bowdoin’s Special Collections and Archives to aid in her research. “I was looking at marginalia, Longfellow’s handwritten notes,” says Abbruzzese. “It was so amazing to think that Longfellow held this, he wrote on it, and here it is at the College where I can hold it and incorporate it into my essay.”

“Longfellow is such a towering, almost mythical, figure at Bowdoin that it’s funny to go back and realize he had difficulties just like everyone else,” she says. “As a young professor, he sometimes butted heads with the administration. In doing this research, he became much more of a real person to me.”

In the essay “John Dayman and H. W. Longfellow: A Discourse on the Art of Translation,” Aisha Woodward ’08 looks at a letter from Longfellow, previously unknown to scholars, which was recently acquired by Bowdoin's Archives and Special Collections.

Woodward traces the evolution of Longfellow’s epistolary friendship with John Dayman, a British translator of Dante who was largely overlooked in his day.

Woodward, currently a PhD student in Italian Literature at Yale, won the prestigious 2008 Dante Prize from the DSA honoring the best undergraduate essay on Dante in North America. That work grew out of an independent study with Saiber at Bowdoin. An earlier version of Abbruzzese's essay earned an honorable mention in the 2007 Dante Prize as well.

Abbruzzese, who currently is a publicist in the Boston area, says her work honing the essay for publication gave her "a chance to continue the academic dialogue begun at Bowdoin."

"I was dealing with Twitter by day and Dante by night," she quipped.

Saiber is a leading Dante scholar and says she is “immensely honored to be teaching his works at Longfellow’s institution. It's wonderful to see students nearly two centuries later sharing his fascination for Dante."