“Holy Sobriety.” Surviving Persecution in Early Twentieth Century Russia

By Tom Porter

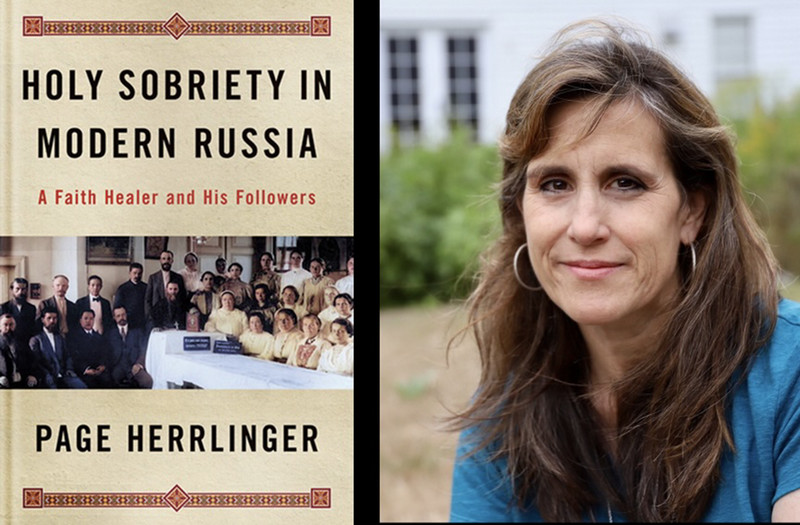

Herrlinger was poring over some photos featuring the charismatic, early twentieth-century spiritual leader Ioann Churikov —someone who had played a small role in her first book, about workers and religious identity in prerevolutionary Russia—when she became aware of someone looking over her shoulder.

“I know them,” said the woman. “Do you want to meet them?” Herrlinger’s initial reaction, she said, was confusion. “I knew Churikov was long dead, so I was puzzled. But she explained there was still a small community of his followers in St. Petersburg. So, I went to visit them and discovered that they even had an archivist. That’s how this project was born,” explained Herrlinger at a recent book launch event on campus to promote her latest work.

Holy Sobriety in Modern Russia: A Faith Healer and His Followers (Northern Illinois University Press, 2023) draws on multiple archives and primary sources, including secret police files, to reconstruct the history of a spiritual movement that survived persecution by the Orthodox church and decades of official atheism and still exists today.

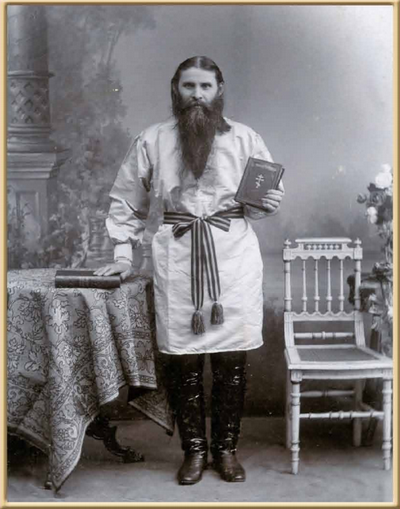

At the center of the story is “Brother Ioann” Churikov (1861–1933), originally a peasant from southern Russia whose deep piety, “miraculous” healing ability, and scripture-based philosophy known as holy sobriety, helped thousands of people reclaim their lives from the devastating effects of alcoholism and other illnesses that went along with the poverty so prevalent in pre-revolutionary Russia, and beyond.

“In the first chapter, I focus on the evolution of Churikov, a one-time tavern keeper, broken through the death of his wife and daughter, who saved himself through scripture. He wanted to be useful to people and did a lot of spiritual wandering, ending up in St. Petersburg, where he witnessed the effects of modern industrial society on people and began trying to help them through his preaching.”

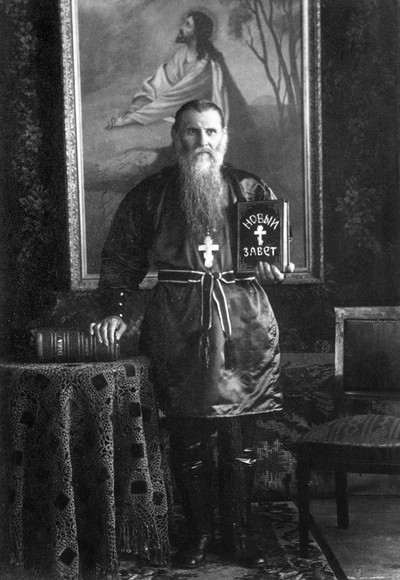

Churikov amassed such a large following through his healing and preaching—around a hundred thousand by the time of the Russian Revolution—that the Orthodox Church viewed him with suspicion, as someone who was corrupting the faith and usurping their power. Churikov found himself incarcerated several times, including in a mental institution, before he was excommunicated in 1914.

Churikov and his followers in the prayer house at Vyritsa in 1911. Plaques on table read: “As for me and my house, we will serve the Lord,” (Joshua 24:15) and “whoever comes to me, I will never cast out,” (John 6:37).

After the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, explained Herrlinger, life initially got better for Churikov and his followers, who were viewed sympathetically as people who had been persecuted by the Tsarist regime.

“They set up a faith-based agricultural commune outside St. Petersburg, where they were very productive, as you might expect sober workers to be, even winning awards from the atheistic state for their efficiency.” This ended in 1929, she said, when Stalin cracked down on all religions and collectivized the peasants. Churikov was imprisoned, along with many of his followers, and in 1933 he died behind bars.

Through Churikov’s followers, the movement lived on, albeit underground, and Herrlinger’s book is as much about them as it is about the man himself.

“As I researched the archive, I was really lucky to find the testimonies of many followers. It took a long time to go through these stories and contextualize them,” said Herrlinger.

Two groups of followers emerged in the years following his death, she explained, and these groups still exist today. “One group believes Churikov was actually the second coming of Christ. To the other group, Churikov remains simply a righteous person, an inspirational figure.” In the post-Soviet era, this second group—the non-messianic one—has now actually been integrated back into the Russian Orthodox Church, explained Herrlinger.

“It’s truth that’s stranger than fiction,” she added, reflecting on the story of “Brother Ioann” and his “Holy Sobriety” movement. “It’s also an important story, embodying as it does themes that are so common in Russian history—of faith, community, persecution, and resilience.”