Dates:

Location:

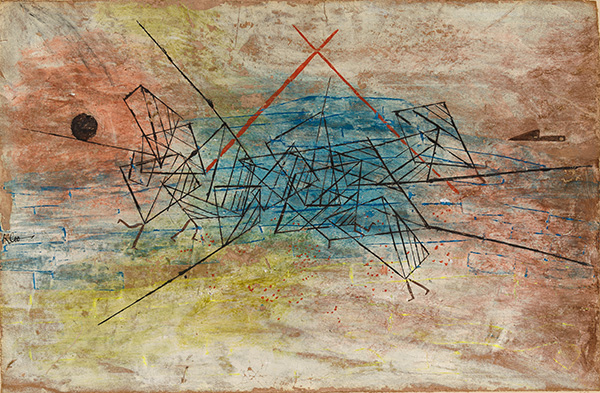

Shaw Ruddock GallerySelected Works

About

The Bauhaus, a pioneering German art school, redefined the pedagogy of art and craft, fostered relations between art and industry, and systematically explored the impact of design and architecture on their users and occupants. The school was founded in Weimar on April 1, 1919 and successively moved to Dessau in 1925 and Berlin in 1932. Founding director Walter Gropius conceived the Bauhaus during WWI as a means for a devastated civilization to rebuild itself. He engaged some of the most prominent artists of the era as Masters, including Lyonel Feininger, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Oskar Schlemmer, and Lásló Moholy-Nagy. Focused on economy and efficiency, Gropius established an internationalist approach, centered on the machine as a democratizing force in the service of social betterment. The geometric clarity and embrace of new materials and production techniques favored by Bauhaus artists and designers quickly became synonymous with Modernism.

The Bauhaus developed an interdisciplinary curriculum. At its core were a foundational course on artistic theory and study of materials, the so-called Preliminary Course, and experimental, craft-based studios, or Workshops, under the joined direction of artists and craftspeople. The Preliminary Course was an obligatory six-month introductory program. The course offered elementary instruction in the areas of form, color theory, and materiality, achieved through practical experimentation across mediums. Unlike students in traditional art academies, who were instructed to copy styles and techniques used by old masters, Bauhausler were encouraged to innovate, using the inherent characteristics of various materials to inspire and direct form.

Each Bauhaus workshop was divided into craft and form. Instruction in craft, taught by a master craftsman, dealt primarily with the materials and tools specific to that workshop, as well as the practical elements of book-keeping, estimating, and contracting. Instruction in form, taught by an artist, was more theoretical and revolved around observation, representation, and composition. During the Weimar period workshops were established for sculpture, carpentry, metal, pottery, stained glass, wall-painting, and weaving, each notably working with a different material. As the school evolved, workshops were added to accommodate printing, advertising, the stage, and furniture.

Gropius described the workshops as “a practical first step in mastering industrial processes,” reminding that the workshops’ ultimate goal was the development of designs to be manufactured and made widely available to the public. Through the workshops, the Bauhaus aimed to redefine standards of excellence in design and revolutionize modern material culture. Moreover, Gropius believed that such craft-based training was a prerequisite for work in architecture.

Based on the conviction that form follows function, Walter Gropius created the Bauhaus to mold a new generation of architects and designers that would change the overall structure, appearance, and functionality of the built environment. The purest architectural manifestation of the Bauhaus’ ideas is the Dessau school building itself and the surrounding masters’ houses. Completed by Gropius’ architectural office, the buildings were designed to maximize the intake of natural light, ease of transit from one area to another, and adaptability, should it ever be required that the spaces change from their original function. Gropius claims that the school virtually “designed itself,” as its plan was based only on the requirements of the workshops and the social life of the school. It was this sort of functionally-minded design that defined Bauhaus architecture.

In 1933, the Bauhaus was closed by National Socialist officials. Former masters and students dispersed across the continent and the world, founding schools based on Bauhaus principles in the United States and elsewhere. Walter Gropius took the helm at Harvard’s Department of Architecture. The 100th anniversary of the school’s founding marks an opportunity to reflect on the origins of the modernist tradition and the contributions of individuals who helped with its codification.

Walter Gropius, from the Bauhaus Manifesto, 1919

The ultimate goal of all art is the building! […] Architects, sculptors, painters - we must all return to craftsmanship! For there is no such thing as ‘art by profession.’ There is no essential difference between the artist and the artisan. […] So let us therefore create a new guild of craftsmen, free of the divisive class pretensions that endeavored to raise a prideful barrier between craftsmen and artists! Let us strive for, conceive and create the new building of the future that will unite every discipline, architecture and sculpture and painting, and which will one day rise heavenwards from the million hands of craftsmen as a clear symbol of a new belief to come.

Press

Enjoy these articles about the exhibition

Museum News, February 25, 2019

Bowdoin News, February 28, 2019

Bowdoin Orient, March 29, 2019

Maine Sunday Telegram, March 31, 2019