History/ES 247 Reading Guide

The Encounter in Maine and Northern New England

- Christopher Bilodeau, “Creating an Indian Enemy in the Borderlands: King Philip’s War in Maine, 1675-1678,” Maine History 47.1, (2013), 11-41. (e-reserve)

- Emerson W. Baker and James Kences, “Maine, Indian Land Speculation, and the Essex County Witchcraft Outbreak of 1692,” Maine History 40:3 (Fall 2001): 159-189. (e-reserve)

- Mary Beth Norton, “George Burroughs and the Girls from Casco: The Maine Roots of Salem Witchcraft,” Maine History 40:4 (Winter 2001-2002): 259-278. (e-reserve)

Further reading:

- Emerson W. Baker, “Finding the Almouchiquois: Native American Families, Territories, and Land Sales in Southern Maine, Ethnohistory 51.1 (2004), 73-100. (JSTOR)

- Bruce J. Bourque and Ruth Holmes Whitehead, “Tarrentines and the Introduction of European Trade Goods in the Gulf of Maine,” Ethnohistory 32.4 (1985)

- Emerson W. Baker, “‘A Scratch with a Bear’s Paw’: Anglo-Indian Land Deeds in Early Maine,” Ethnohistory 36.3 (1989).

- Alfred W. Crosby, “Ecological Imperialism: The Overseas Migration of Western Europeans as a Biological Phenomenon,” in Donald Worster, ed., The Ends of the Earth: Perspectives on Modern Environmental History (1988), 103-117.

- Calvin Martin, “The European Impact on the Culture of a Northeastern Algonquian Tribe: An Ecological Interpretation,” William and Mary Quarterly 3d. Ser., 31.1 (1974), 3-26. JSTOR

- Gordon M. Day, “The Indian as an Ecological Factor in the Northeastern Forest,” Ecology 34.2 (1953), 329-346. JSTOR

Christopher Bilodeau presents another side of the contact of cultures—not ecological but diplomatic and military. He offers an interpretation of the first Indian War in Maine that differs from traditional assumptions that the theatre of war in Maine was simply an adjunct to King Philip’s War in southern New England.

- How does he characterize the causes of tension between settlers in Maine and the various tribes in the 17th century settlement areas?

- What series of events led to violence in the summer of 1675? What was the long history behind these new events?

- What misunderstandings about tribal organization and allegiance heightened those tensions and exacerbated colonial reactions to deeds done by individual native Americans?

- Why were the English so prone to assume and spread rumors about French involvement and tribal unrest?

- What does Bilodeau argue about the special nature of the war in Maine, 1675-78, and about its consequences for settlement, both short term and long term?

The articles by Tad Baker & James Kences and by Mary Beth Norton describe different aspects of the origins (economic, political, cultural) and the consequences of King Philip’s [Metacom’s] War (1675-1678) and King William’s War (1688-1692) for settlers on the Maine frontier.

- What do these studies, in conjunction with the other studies of early settlements that we've read, suggest about the nature and process of seventeenth-century settlements in Maine?

- How did the particular economics and politics of trade, land “exchange,” and settlement in Maine—as a negotiation with local Wabanaki tribes that continued to have a strong presence in Maine—shape relations between the two peoples? How did the Wabanaki respond to the gradual but determined encroachment on their land in Maine over the course of the seventeenth century?

- Both articles also draw compelling, but very different connections between the consequences (economic, social, cultural, religious) of the two “Indian Wars” in Maine and the Salem Witchcraft trials in Essex County, Massachusetts, in 1692. Baker and Kences argue that myriad individual purchases and investments connected both the judges and the merchants involved in the witchcraft trials, as well as many Salem townspeople in general to the Maine frontier.

- According to Baker and Kences, how did the process, by which the promise of land speculation in Maine turned suddenly to risk and loss, reinforce, in both general and in specific ways, the social, economic, and religious tensions that fueled the witchcraft outbreak?

- In the minds of late seventeenth-century Puritans, why and in what ways did “Maine” become allied with Satan?

- According to Norton, what were the most significant aspects of the Maine “roots” of Salem witchcraft?

- How does Norton connect the experiences of particular Maine settlers, with either former or future ties to Salem Village, with the patterns of witchcraft accusations in Salem?

- To what extent does it matter that those experiences happened to be gendered in significant ways?

- How does Norton’s argument that the accusations against Burroughs created the pivotal moment in the Salem witchcraft hysteria both enhance and alter our understanding of witchcraft as a community phenomenon?

Further reading:

Day’s article offers an earlier discussion of some of the questions and issues that Cronon addresses in Change in the Land with specific reference to Maine and Northern New England. He was one of the first scholars to attempt to change the questions that we ask about Native Americans—in particular, about their interaction with the environment in which they lived. To do so, Day described a number of Indian practices that modified and changed the environment in the “northeastern forest”—an area which includes Maine and northern New England.

- How, and for what reasons and purposes did native Americans alter their environment? What were some of the consequences of their subsistence practices? How did their practices influence the ecology of the northeastern forest?

- What previous interpretations about Native Americans and about the land that they occupied was Day challenging? How does his account compare and contrast with Cronon’s more extensive account? Does his account add anything new to our understanding?

- How does a fuller understanding of the extent to which Native Americans used and altered their environment help us understand the conflicts between Native Americans and English settlers—over land use, land rights, land ownership, trade, and exchange—that escalated into the First and Second Indian Wars in Maine in the late seventeenth century?

Map of seventeenth-century settlements in Maine.

Map of villages and towns attacked during the First and Second Indian Wars.

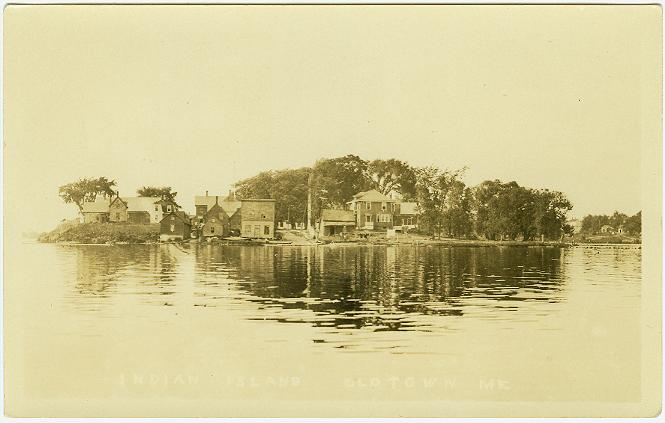

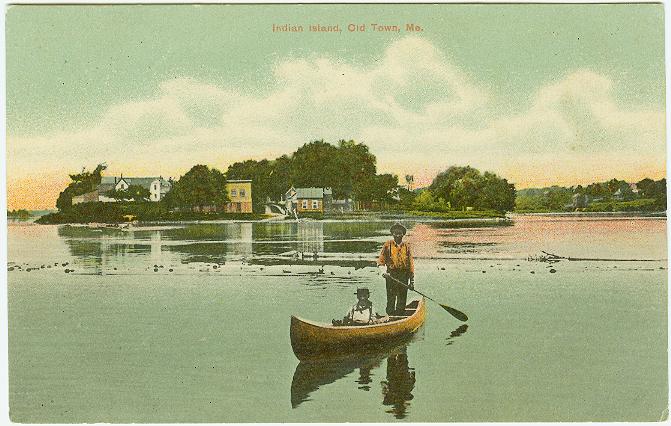

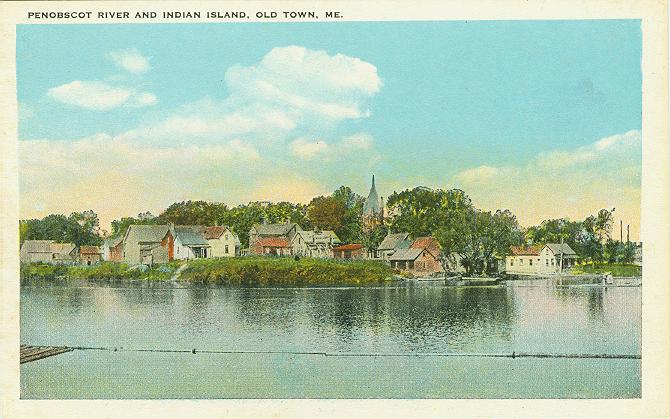

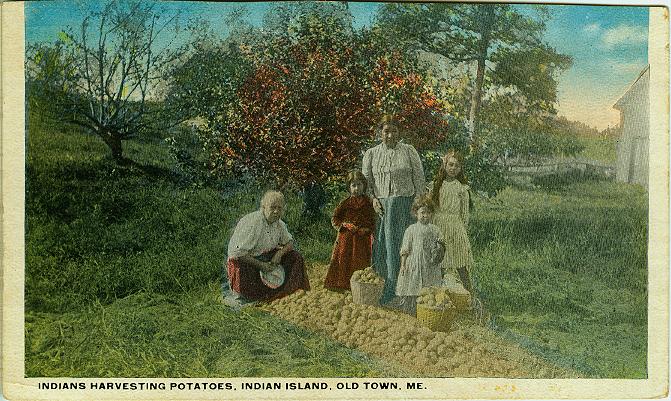

Postcards

[Indian Island, Old Town, ME.] (c. 1910)

Indian Island, Old Town, Me. (c.1906)

Penobscot River and Indian Island, Old Town, Me. (c.1915)

Indians Harvesting Potatoes, Indian Island, Old Town, Me. (c.1915)

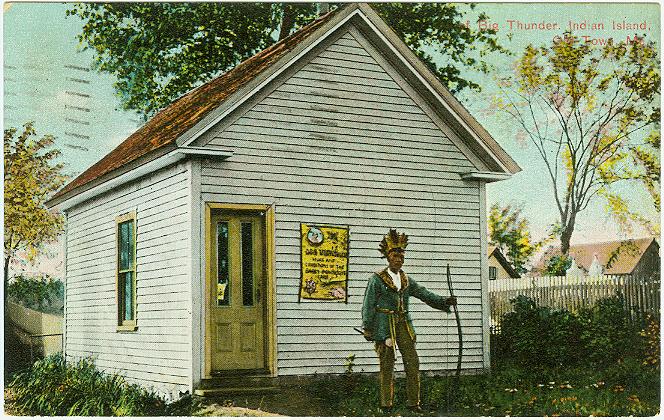

Chief Big Thunder, Indian Island, Old Town, Me. (c.1908)

Gala Day on Indian Island. June 27, 1921. Note the Plains-style tipis.

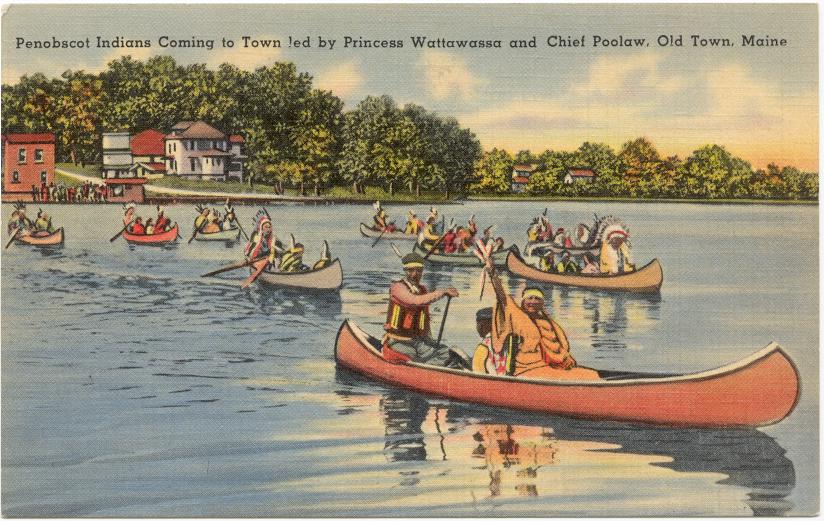

Penobscot Indians Coming to Town led by Princess Wattawassa and Chief Poolaw, Old Town, Maine. (c.1940)

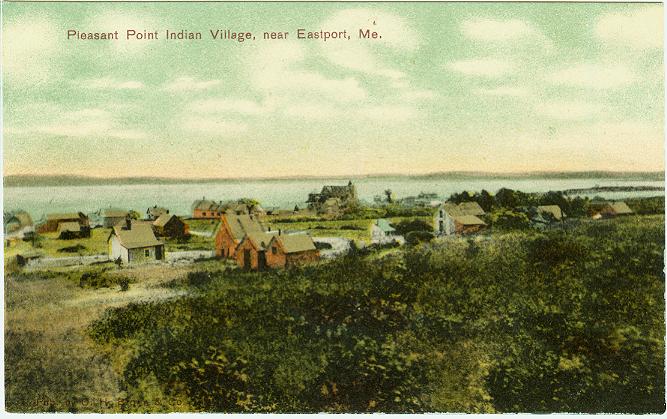

Pleasant Point Indian Village, near Eastport, Me. (n.d.)