The Triumph of Caesar - The Elephants

The Triumph of Caesar - The Elephants

Andrea Andreani

Italian, 1599

Woodcut on paper

14 1/2 in. x 14 5/8 in. (36.83 cm. x 37.15 cm.)

1965.47

The spectacle of triumphal military processions in ancient Rome fascinated early modern European elites, many of whom hoped to mimic the same display of power, wealth, and magnanimity in their own lives. In the 16th and 17th centuries, political marriages and diplomatic visits primarily provided the occasion for nobility and royalty to express these desires. This woodcut print, depicting the section of the triumphal procession featuring elephants captured by Julius Caesar, is the sixth out of ten prints made by Andrea Andreani that faithfully reproduced Andrea Mantegna’s earlier Triumphs of Julius Caesar frescoes from the Gonzaga ducal palace in Mantua. Mantegna’s Triumphs of Julius Caesar was universally admired for the purported faithfulness to which the artists illustrated Caesar’s triumph as described by ancient writers and read by many European elites in their formal educational years.

(B. Wu)

Trajan’s Column

Trajan’s Column

Giovanni Battista Piranesi

Italian, 1758

Etching on cream laid paper

28 15/16 in. x 20 3/8 in. (73.5 cm. x 51.75 cm.)

Gift of Charles Pendexter, 2009.16.589

Towering at around 126 ft, the Column of the Roman emperor Trajan (98–117C CE) was one of the most popular attractions for Grand Tour visitors to Rome. Artists visited this monumental site to copy the sculptural reliefs, architects drew inspiration for their own monumental designs, and scholars and visitors alike marveled at the wealth of information the column provided about the ancient Roman Empire. Piranesi’s print of Trajan’s Column was as popular for those who wanted a keepsake of one of the foremost highlights of Rome as it was for those who could not make their own visit to the Eternal City. In this etching, Piranesi captured the dramatic experience of seeing the monument using a perspectival view that accentuated the impressive scale of the Column. The exaggerated body language of the small Grand Tour visitors at the ground illustrated the awe of seeing Trajan’s Column in person for the first time.

(B. Wu)

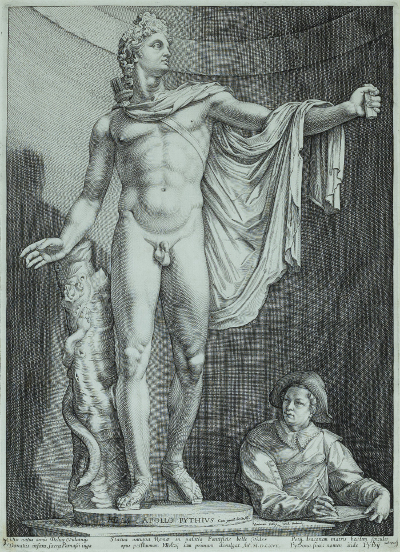

Apollo Belvedere

Apollo Belvedere

Hendrick Goltzius

Dutch, ca. 1592

Engraving on cream laid paper

17 5/16 in. x 12 3/16 in. (43.97 cm. x 30.96 cm.)

Gift of Charles Pendexter, 2009.16.341

The Apollo Belvedere, a 2nd century CE Roman marble copy of an earlier Greek bronze, has enchanted artists, scholars, and visitors since its rediscovery at the end of the 15th century. The allure of this sculpture, and others like it, was further magnified by artists who illustrated ancient works in easily disseminated forms. Consequently, artists contributed to the development of antiquarian interests by promoting certain classical pieces as “must-see” attractions of the Grand Tour. Golztius’ print both captures the magnificence of the Apollo Belvedere and alludes to the artist’s influential role in disseminating the interest of, and appreciation for, classical works through the depiction of a young artist drawing in situ in the lower right corner, behind the statue.

(B. Wrubel)

The Pyramid of Caius Cestius

The Pyramid of Caius Cestius

Giovanni Battista Piranesi

Italian, 1756

Etching on ivory laid paper

15 5/16 in. x 21 ¼ in. (38.89 cm. x 53.98 cm.)

Bequest of Mrs. Morgan B. Cushing, 1960.54

This picturesque etching by Piranesi depicts the Pyramid of Caius Cestius, built as a monumental tomb for the Roman praetor at the end of the 1st century BCE. This etching is part of a larger series produced by Piranesi and called the Vedute di Roma (“Views of Rome”). The design of the pyramid was influenced by those built in ancient Egypt, though it rises at a much steeper angle. This pyramid is a physical example of Roman spectacle through its immense size, illustrated through the comparison of the massive structure to the people standing at the bottom of the etching. An exotic and unique monument, the pyramid became an important Roman stopping point on the Grand Tour and remains a highlight today.

(M. Brown)

Apollo and Daphne

Apollo and Daphne

Jacopo da Carrucci (called Pontormo)

Italian, 1513

Oil on canvas

24 3/8 in. x 19 1/4 in. (61.91 cm. x 48.9 cm.)

Gift of the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, 1961.100.9

Pontormo's canvas depicts the love-struck Apollo chasing Daphne, who was shot with a blunt leaden shaft, inciting antipathy. Growing exhausted from his relentless pursuit, Daphne implores her river god father to save her. The chaste maiden’s prayers are answered. Just as Apollo is about to overtake her, she is transformed into a laurel tree. In Pontormo’s painting, we witness the initial instant of Daphne’s transformation, branches springing upward from her arms, while the rest of her body still retains its human form. The grieving Apollo adopted the laurel as his sacred plant in memory of his beloved, and the crown wreathed with its leaves came to be appropriated in celebration of poets and public triumphs. Renaissance Carnivals Florence’s Carnevale of 1513 carried special significance, as it marked the first such occasion since the return of the Medici after eighteen years in exile. Pontormo’s pair of small mythological scenes, preserved here and in a painting in the Samek Museum at Bucknell University (a gift, like this one, of the Samuel H. Kress Foundation) were jointly conceived for the elaborate ritual as part of a much larger program of painted and sculpted ephemera. Together, the carefully choreographed decorations served to mark a particularly charged political and social event. The turn in political fortunes, already signaled during Carnevale, was strongly reinforced just a month later, with the election of Giovanni de’ Medici as Pope Leo X in Rome. Only eighteen at the time, Pontormo was entrusted with a project of great personal prestige.

(Museum)