"Corinthian Style" Bronze Helmet

"Corinthian Style" Bronze Helmet

Greek, ca. 650-575 BCE

Bronze

11 1/2 in. x 9 in. x 7 in. (29.21 cm. x 22.86 cm. x 17.78 cm.)

Gift of Edward Perry Warren, Esq., Honorary Degree, 1908.1

Bronze helmets like this would have been worn by contestants in the hoplitodromos (“race of soldiers”), an event in ancient Greek athletic competitions during which participants wore metal armor and competed in a footrace. Races such as the hoplitodromos suggest that ancient Greek athletic competitions existed in part to train young boys and men for warfare and instill a military culture in larger male society. This helmet is an example of a type ubiquitous across the ancient Greek world, and often referred to as “Corinthian” for its frequent depiction in the arts of that city. The cheek plates and nose guard of the helmet have been bent outward, rendering the helmet unfit for service. This practice is widely attested and suggests the use of military Greek helmets as votive offerings to the Gods for success either in battles or games.

(B. Wu)

Attic Red-Figure Eye Cup by the so-called "Bowdoin Eye Painter"

Attic Red-Figure Eye Cup by the so-called "Bowdoin Eye Painter"

Greek, 520-510 BCE

Terracotta

5 5/16 in. x 16 3/16 in. (13.5 cm. x 41.12 cm.)

Gift of Edward Perry Warren, Esq., Honorary Degree, 1913.2

The interior of this drinking cup depicts an athlete competing in the hoplitodromos (“race of soldiers”), a footrace that was integral to many public games including the Olympics. In the hoplitodromos, men sprinted while carrying shields and helmets in the guise of Greek hoplites, a true test of agility and brawn as this armor weighed approximately twenty pounds. On either side of the vessel’s exterior is depicted an athlete holding halteres (stone weights), shown both before and after the long jump of the Pentathlon. The inscription reading “KALOS” (“beautiful”) extols the athlete and is a common feature of vessels enjoyed during the symposium, the Greek male drinking party.

(B. Wrubel)

Bronze strigil (Scraper) with duck/swan head handle

Bronze strigil (Scraper) with duck/swan head handle

Greek, 500-400 BCE

Bronze

11 13/16 in. (30 cm.)

Gift of Edward Perry Warren, Esq., Honorary Degree, 1912.23

Before training and competing in the nude, Greek athletes would lather themselves in olive oil as a way to protect their skin. The strigil was therefore an essential tool used after training to scrape dirt, sweat and oils off of the body. The curved shape of the blade was designed to be able to clean all the different parts of the body. This particular tool ends in a swan's head and present an inscription incised on the back side in Greek letters, Diotimos Athenaios, who may have been the maker or owner of the strigil.

(M. Brown)

Round Tesserae with Figures in Relief

Round Tesserae with Figures in Relief

Greek, 400-300 BCE

Terracotta

9/16 in. (1.5 cm.), 5/8in. (1.6 cm.), 3/4 in. (1.9 cm.), 13/16 in. (2 cm.)

Gift of Edward Perry Warren, Esq., Honorary Degree, 1930.53, 1930.59, 1930.66, 1930.63

These four coin-like terracotta disks, or tesserae, likely served as entrance tickets for Greek public festivals. The letters may have corresponded to specific seating sections which were in turn based on socio-economic status, thus reinforcing the hierarchy that existed within the contemporary culture of spectatorship. A large quantity of similar tesserae has been discovered in Athens, where it is possible that these tokens were utilized specifically for the theater performances held during events like the City Dionysia. The images they bear may also suggest that these tokens were used during other types of public spectacles such as athletic events: one token depicts a chariot race while other tesserae present laurel leaves that would have crowned victors.

(B. Wrubel)

Miniature mask of a “satyr” and miniature mask of a “youth”

Miniature mask of a “satyr” and miniature mask of a “youth”

Greek, 3rd-2nd century BCE

Terracotta

2 13/16 in. x 1 ⅜ in. (7.2 cm. x 3.5 cm.); 1 3/4in. x 2 3/8 in. (4.5 cm. x 6 cm.)

Gift of Mr. Dana C. Estes, Honorary Degree, 1902.42, 1902.43

Terracotta representations of masks are an important evidence for understanding how the masks worn by actors in Greek theater performances may have appeared. Such theatrical masks were made from organic materials that did not survive to the present day. The masks allowed for a male actor to play multiple characters during a single performance. These decorative copies in miniature have holes in the top so that the masks could be hung on a wall. One mask is of a beardless youth wearing a thick wreath of ivy wound with a ribbon. The other represents a bearded satyr wearing an ivy crown. Youths and satyrs were commonly characters of comedic plays.

(M. Brown)

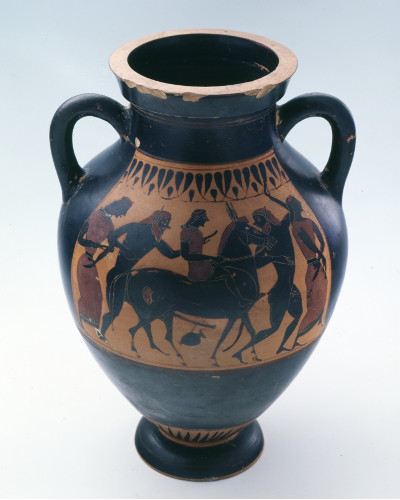

Black-Figure Amphora

Black-Figure Amphora (side A: Dionysus with Maenads and Satyrs) (side B: The Return of Hephaistos)

Greek, 550 BCE

Terracotta

12 ½ in. x 8 ¼ in. (31.8 cm. x 21 cm.)

Gift of Edward Perry Warren, Esq., Honorary Degree, 1915.44

Dionysus, the Greek god of theater and wine, appears on this amphora. On one side, he is represented cavorting and drinking with his attendants, Maenads and Satyrs. The opposite side of the amphora, instead, captures a moment of a Greek myth, "the return of Hephaestus," who appears as riding a donkey. This panel shows the comical aspect of theater in that the donkey has a vessel hanging on its erect phallus. Since we do not have access to the actual performances, the recreations of mythological scenes on amphoras or other ceramics meant for popular consumption allow us to imagine their interpretation in Greek theater.

(M. Brown)