Two-Faced (Double Visage), Faces of Mask series, 2015–2017

Hervé Youmbi

Cameroon, born 1973

Two-Faced (Double Visage), Faces of Mask series, 2015–2017

plastic, animal fur, hair, cowrie shells, beads, paper, shipping crate, video, and photograph

Mask height 52 inches (132.08 cm)

Photograph 15 x 19 inches (38.1 x 48.3 cm)

Shipping crate 22 1/2 x 46 x 22 1/8 inches (57.2 x 116.8 x 56.2 cm)

Museum Purchase, Lloyd O. and Marjorie Strong Coulter Fund

2019.26.a–d

Interested in challenging notions of authenticity, contemporary artist Hervé Youmbi recalls witnessing a funerary dance in Cameroon where participants wore mass-produced North American masks. In response, Youmbi produced contemporary masks in collaboration with other artists. They took a well-recognized mask from the Scream film series and added a crown of horns, dreadlocked coiffures, and cowrie-studded surfaces—visual elements commonly seen in Yegue masks from Ku’ngang, a religious society among Bamiléké people in Cameroon. Youmbi includes the mask’s shipping crate with transport documentation in the display to highlight the mask’s movements. At the artist’s direction, the mask could travel back to Cameroon for future performances if warranted. With each move, the mask’s status fluctuates between contemporary art, performance, and ethnographic artifact, raising questions of the identity of this work and the role of “ethnographic” practice in contemporary art.

Two-Faced (Double Visage), Faces of Mask series, artist label, 2015-2017

Hervé Youmbi

Cameroon, born 1973

Two-Faced (Double Visage), Faces of Mask series, artist label, 2015-2017

plastic, animal fur, hair, cowrie shells, beads, paper, shipping crate, video, and photograph

Museum Purchase, Lloyd O. and Marjorie Strong Coulter Fund

2019.26.a–d

Artist label

Bamiléké Yegué Scream Mask

Hervé Youmbi (b. 1973), produced in the workshops of Alassane Mfouapon (carver), Frédéric Feudjeueck (coiffure), and Marie Kouam (beader)

West region, Cameroon

Bamiléké yégué mask depicting the character Ghostface.

wood, hair, animal skin, beads, cowries, pigment and cloth

2015-2017

Hervé Youmbi commissioned this mask to be used in the Ku’ngang Society. Society elders approved the mask, although it deviates from the stylistic conventions of a Bamiléké yégué mask by integrating the popular Halloween mask of Ghostface, a character in in Wes Craven’s 1996 film Scream, inspired by Edvard Munch’s painting The Scream. After an exhibition during 2015 at Bandjoun Station, opened by Cameroon’s Minister of Culture, Mrs. Ama Tutu Muna, the mask was ritually activated and performed by David Ngueliatuo at a funeral ceremony at Bandja on February 21, 2016. It was also performed at a Kun’ngang Society ceremony at Bakoven-meka village, which Hervé Youmbi filmed on March 5, 2016. In October 2016, the activated mask was exhibited in “Visages de Masques” at Doual’art, Douala, Cameroon, after which it was returned to the West region. In October 2017, the mask traveled to New York for exhibition in “Unmasked” at Axis Gallery.

Hervé Youmbi

(b.1973, Central African Republic; lives and works in Douala, Cameroon)

Two-Faced / Double Visage: Bamiléké Yegué Scream Mask, 2015 - 2017

multi-media

Hervé Youmbi commissioned this mask as a component of his series Two-Faced Mask / Double Visage, a part of his ongoing project Visages de masques, which explores the reception and commodification of African art forms both within African ritual communities and by outsiders. In the West, African art is generally classified according to a “one tribe, one style” formula. However, in Youmbi’s native Cameroon, sculptors often draw inspiration from other cultures. In this project, Youmbi probes the limits of what is ritually acceptable as a Bamiléké mask.

The status of the “Two-Faced Mask / Double Visage” as art object changes according to the display contexts of the ceremonial dance or the art gallery, unsettling the supposed stable identity of the artwork. Similarly, Hervé Youmbi’s role as contemporary artist involved commissioning the artwork from several specialists for another person to perform, while Youmbi adopted the ethnographer’s role of “participant observer” to record “his” object being performed by a Ku’ngang Society member.

Male power figure (Nkisi), date unidentified

Artist unidentified

Songye peoples, Democratic Republic of the Congo

Male power figure (Nkisi), date unidentified

wood, cowrie shells, and horn

height 13 7/16 inches (34.2 cm

On loan from the Wyvern Collection

Once used to facilitate contact with spirits, this power figure in Songye society later played a role in inspiring the development of Cubism. George Braque, who later owned this power figure called an nkisi, appreciated the geometrical and expressive style found in so-called “primitive art”—a term that referred to objects created by artists operating outside of European standards. Such work was believed to represent a more “authentic” form of expression by modernists eager to free themselves from European traditions. Interest among European and American artists in aesthetic qualities of African art, however, often disregarded the work’s use and meaning among communities in Africa.

Amanda Banasiak ’19

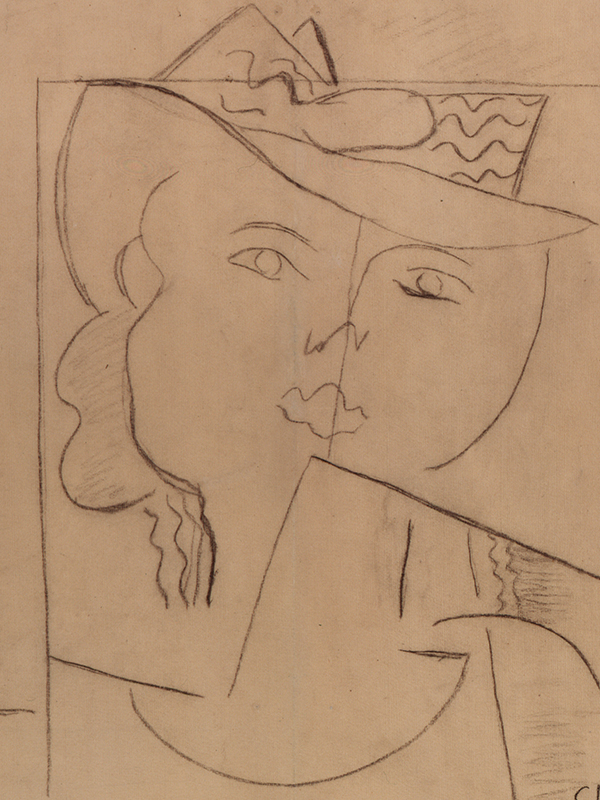

Head of a Woman (Tête de Jeune Femme), ca. 1920–1922

Georges Braque

France, 1882–1963

Head of a Woman (Tête de Jeune Femme), ca. 1920–1922

crayon on paper

18 15/16 x 25 inches (48.1 x 63.5 cm)

Bequest of William H. Alexander

2003.11.14

Once used to facilitate contact with spirits, power figures in Songye society in the Democratic Republic of the Congo later played a role in inspiring the development of Cubism. George Braque, who later owned the power figure from Songye society on view in this exhibition, appreciated the geometrical and expressive style found in so-called “primitive art”—a term that referred to objects created by artists operating outside of European standards. Such work was believed to represent a more “authentic” form of expression by modernists eager to free themselves from European traditions. Interest among European and American artists in aesthetic qualities of African art, however, often disregarded the work’s use and meaning among communities in Africa.

Amanda Banasiak ’19

Head, date unidentified

Artist unidentified

Possibly Sapi peoples, Sierra Leone

Head, date unidentified

soapstone

height 7 1/2 inches (19 cm)

On loan from the Wyvern Collection

One of a small number of stone heads from the region of present-day Sierra Leone, this object, with its highly individualized range of hairstyles, facial features, facial hair, and ornamentation, likely represented a portrait of a powerful individual. The culture that carved these stone heads and the date when it was made has yet to be clearly identified, though other stone heads like this one date to around the fifteenth to seventeenth centuries, possibly earlier. Based on stylistic similarities in hairstyle and facial features found on figural representations in ivory carvings produced for European traders, scholars have attributed these stone heads to ancestors of present-day Mende peoples that sixteenth-century Portuguese traders called Sapi. This naming exemplifies another facet to the complex and longstanding artistic exchanges that have transpired between Europeans and Africans, and how the past continues to inform ongoing conversations today around cultural appropriations.

Ben Wu ’18