Female figure (nyeleni), nineteenth century

Artist unidentified

Bamana peoples, Mali

Female figure (nyeleni), nineteenth century

wood and metal

23 1/2 inches (59.7 cm)

On loan from the Wyvern Collection

This female figure is a nyeleni, which in Bamana language means “pretty little one” or “little ornament.” A carver made this nyeleni with abstract, geometric figural features that become visual symbols emphasizing the figure’s femininity. It represents an idealized female body from the perspective of Bamana men, which echoes a Bamana song:

“A well-formed girl is never disdained,

Her breasts completely fill her chest,

Her buttocks stood out firmly behind,

Look at her slender, young bamboo-like waist…”

Education for young Bamana men includes learning about many aspects of Bamana life, from farming to cultural views towards gender roles. Young men seeking future wives in neighboring towns carry nyeleni figures to remind elders and eligible women that they are looking for partners.

Mustafa Aydogdu ’22

Female initiation mask, date unidentified

Artist unidentified

Mende peoples, Sierra Leone

Female initiation mask, date unidentified

wood

height 16 inches (40.6 cm)

On loan from the Wyvern Collection

Carved from the trunk of a fully-grown tree, this representation of the guardian spirit Sande belongs to one of the only documented female masking practices in West Africa. Wearing helmet-shaped masks like this one was a focal point for celebrations at female initiation ceremonies. In its complete form, an additional head and horns would have projected from atop its rounded base. The mask expresses idealized feminine beauty and power through an elaborate coiffure, smooth broad forehead, small composed mouth, and sensuously ringed neck. Narrowly slit eyes suggest silent contact with spirits, while a slight beard denotes intelligence equal to that of men.

Olivia Muro ’20

Female figure, mid-eighteenth to nineteenth centuries

Artist unidentified

Baga peoples, Guinea

Female figure, mid-eighteenth to nineteenth centuries

wood and palm oil

height 21 3/4 inches (55.3 cm)

On loan from the Wyvern Collection

This standing figure represents the universal mother for Baga people called D’mba. The figure’s form portrays D’mba as a strong and stable woman in her prime—past the age of motherhood—and therefore the peak of what Baga women may hope to achieve. Baga people say that D’mba is wise, represented in the intricate designs on the side of the figure’s head that express age and wisdom. Baga people believe D’mba gives strength to young women, inspiring them to bear children among other powers. Baga cultural practices celebrating D’mba include ceremonies to promote fertility in the land and people.

Samuel Honegger ’20

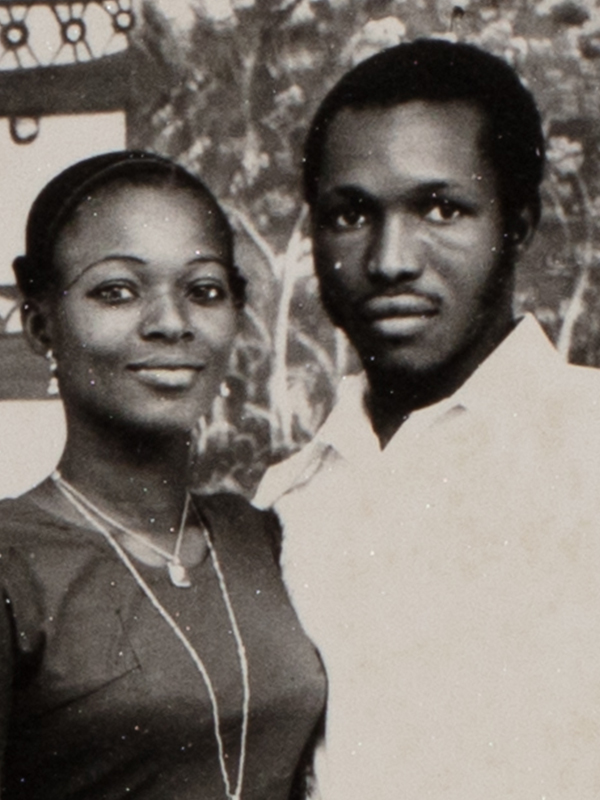

Untitled, 1970s

Malick Sidibé

Mali, 1935–2016

Untitled, 1970s

vintage gelatin silver print

Museum purchase, 2014.22.1

“It’s a world, someone’s face,” Malick Sidibé said in 2010. “When I capture it, I see the future of the world.” Known for his portrait photographs of Malians in the years after independence from France in 1960, Sidibé brings to life subjects ranging from burgeoning pop culture and youth clubs to everyday households. These portraits taken in Mali’s capital Bamako represent the artist’s approach to studio photography. In each photograph, Sidibé posed the sitters against patterned and painted backgrounds, which contrast with their dress. Sidibé’s portraits record the optimistic period of modernization that followed the end of the colonial era.

Untitled, 1970s

Malick Sidibé

Mali, 1935–2016

Untitled, 1970s

vintage gelatin silver print

Museum purchase, 2014.22.2

“It’s a world, someone’s face,” Malick Sidibé said in 2010. “When I capture it, I see the future of the world.” Known for his portrait photographs of Malians in the years after independence from France in 1960, Sidibé brings to life subjects ranging from burgeoning pop culture and youth clubs to everyday households. These portraits taken in Mali’s capital Bamako represent the artist’s approach to studio photography. In each photograph, Sidibé posed the sitters against patterned and painted backgrounds, which contrast with their dress. Sidibé’s portraits record the optimistic period of modernization that followed the end of the colonial era.