Paleoceanographer Michèle LaVigne Picks Up a New Skill: Influencing Policy

By Rebecca Goldfine. Photographs by Michele StapletonAssociate Professor of Earth and Oceanographic Science Michèle LaVigne is participating in a yearlong training program for earth scientists to explore ways to apply her expertise to policy making.

Reconsidering the Role of Scientists

When LaVigne was in a graduate school, she picked up on the tacit understanding that serious scientists, in their quest to uncover empirical truths, should focus solely on their research. To contribute to politics or to educating the public signaled that you may be distracted and even, perhaps, a bit of a dilettante.

But as global warming has progressed, and more people around the world suffer its effects, this stance has shifted. "I’ve seen our field expand the ways we’re using our science beyond traditional research and publishing in academic journals," LaVigne said. "Going to science conferences over the last ten years, I have seen more sessions and programming supporting outreach, education, and communication."

As a professor of undergraduates and a mother of two children, LaVigne said she's extra motivated to add her voice to the national discourse. "I have two young kids who are three and seven, and when they grow up I want to be able to tell them I leveraged my science, skillset, and position of privilege to have the biggest impact I could on the issue of climate change."

“I study climate change and the ocean in the past, and some of the research areas I have published in have been fairly focused and niche. I wanted to expand my impact on this major issue of climate change.”

—Michèle LaVigne

Hearing from the Lab

In 2018, LaVigne's professional association, the American Geophysical Union (AGU), launched an advocacy program for its members called Voices for Science. In two yearlong tracks—one focused on policy and the other on communications—the AGU gives researchers the skills to advocate for federal funding for their fields and for government initiatives grounded in sound science. LaVigne applied and was accepted into this year's twenty-member policy cohort.

With support from the AGU, LaVgne scheduled her first meeting this summer with staff from the offices of Sen. Susan Collins, Sen. Angus King, and Rep. Chellie Pingree—three of Maine's four congressional representatives. In a virtual visit, LaVigne stressed how important grants have been to her paleoceanographic scholarship, which examines past conditions of the ocean, including previous climate changes.

"I spoke about federal science funding," she said. "I was able to share my story and my research and show how it is relevant to Maine, and to offer myself as a resource for other ocean science issues that might come up."

Specifically, she described how her involvement with an ocean acidification group in Maine made up of policy makers, fishermen, and scientists had inspired her to begin reconstructing a history of climate change in the Gulf of Maine.

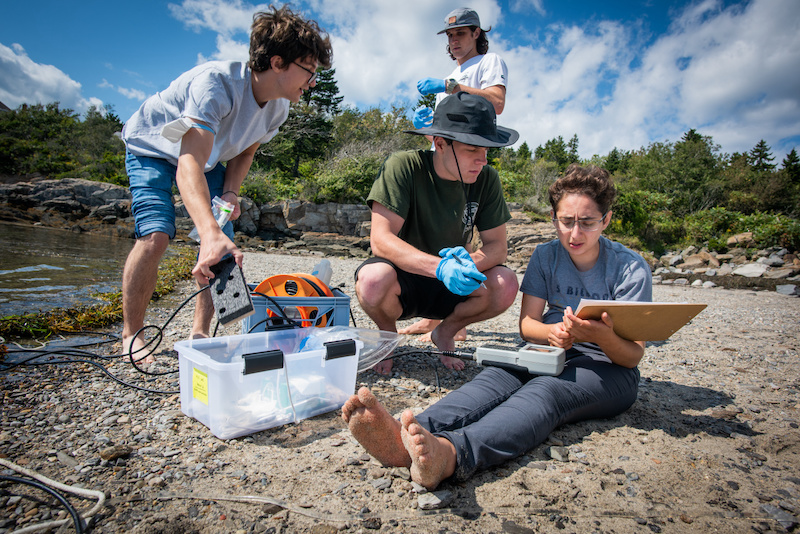

With collaborators from Iowa State University, Claremont College, University of Bristol, and Hamilton College*, LaVigne is investigating the last two centuries of ocean history—the "relatively recent geologic past" since humans began altering Earth systems with activities like burning fossil fuels and industrializing agriculture.

"We don’t have a long record of ocean acidification, because it's more challenging to measure than changing ocean temperatures and salinity. But how can we enact a policy to mitigate ocean acidification if we don’t have a historical baseline to see how much it has changed?" LaVigne noted.

While the ocean is acidifying as it absorbs carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, the change is not happening uniformly. Some areas have a higher pH level than others, a variability affected by ocean currents and other factors.

"It's important to understand how those processes are coming together to predict how this region will change," LaVigne said, adding that her work in this area could have practical applications, such as "helping folks who are setting up aquaculture farms figure out what locations are more susceptible to acidification."

Encouraging Future Citizen Scientists

As she becomes more accustomed to speaking with politicians and contributing to national debates, LaVigne is also hoping to inspire her own students to consider the ways they can wield their knowledge and experience. Increasingly, she's asking students in her classes to not just turn in lab reports and research papers, but also to practice writing policy memos and op-eds.

"Traditionally when scientists did this type of outreach work that didn't result in a journal article, it was seen as extra," she said. "But we’re reevaluating that in my field, and so by giving students credit beyond research and scientific writing helps them to recognize that this is also an important part of being a scientist."

On her first day of class this semester, when she was describing the syllabus and course objective for Research in Oceanography: Topics in Paleoceanography, she told her students about her enrollment in Voices of Science this year.

"My hope is by demonstrating that this is an important part of my time, that this too is part of the role of being a scientist," she said. "This can help show that there are many different ways to be a scientist and to use your science."

* The collaboration of LaVigne with Alan Wanamaker, Branwen Williams, Joseph Stewart, and Aaron Strong is supported with funds from the National Science Foundation and Maine Sea Grant, which is funded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.