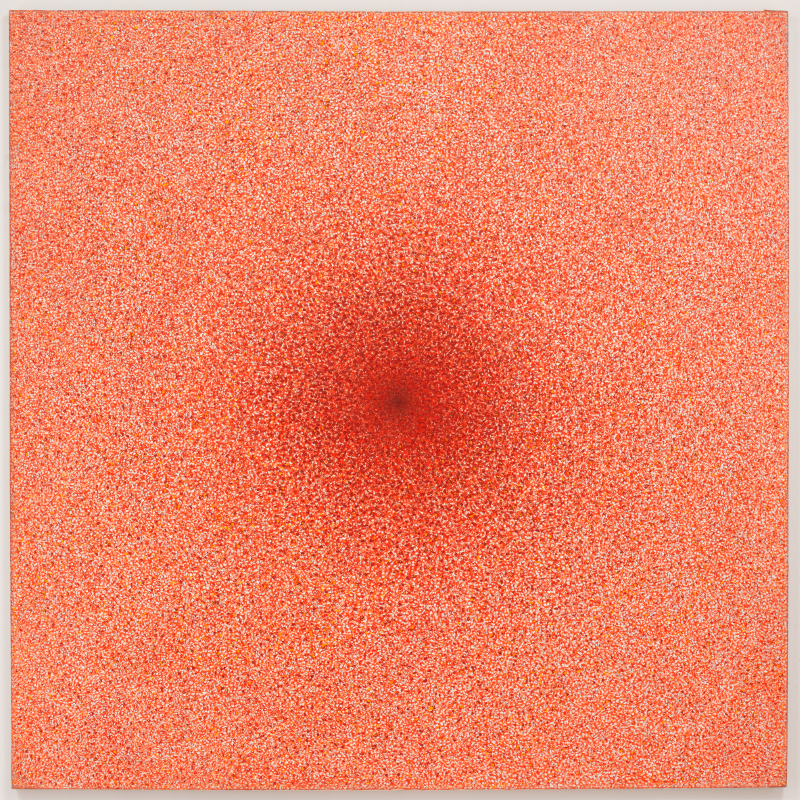

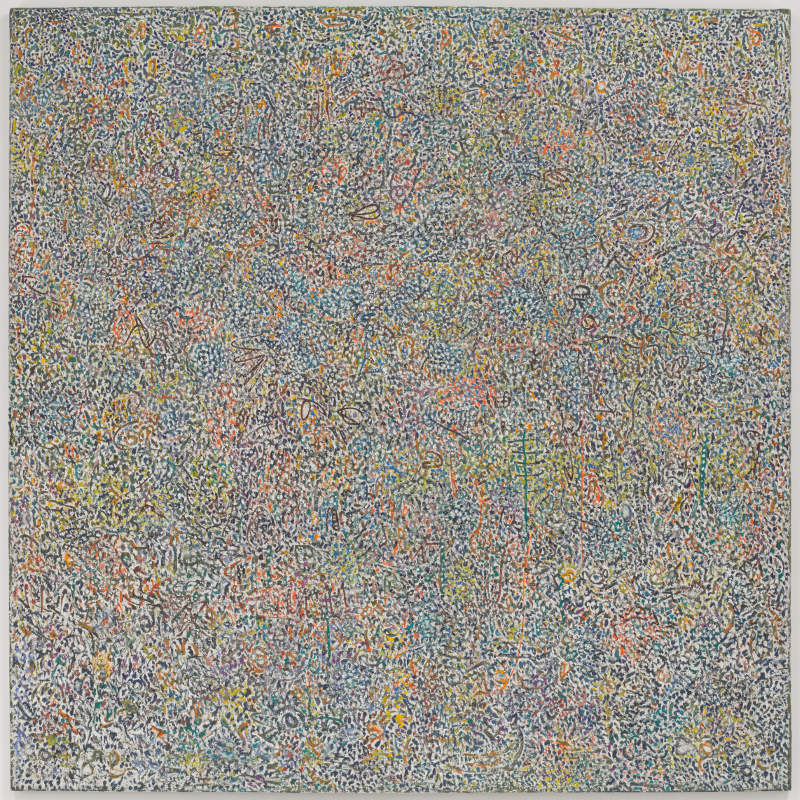

Radiance Number 8 (Imploding Light Red), 1973-74, oil on linen by Richard Pousette-Dart

Radiance Number 8 (Imploding Light Red), 1973-74, oil on linen by Richard Pousette-DartPousette-Dart: Painting | Light | Space

Richard Pousette-Dart (1916—1992) was the youngest artist among the founders of the New York School. This exhibition focuses on paintings from the 1960s and early 1970s, a fruitful period in Pousette-Dart’s career in which his work was widely exhibited, championed by critics, and left a mark on a younger generation of artists.

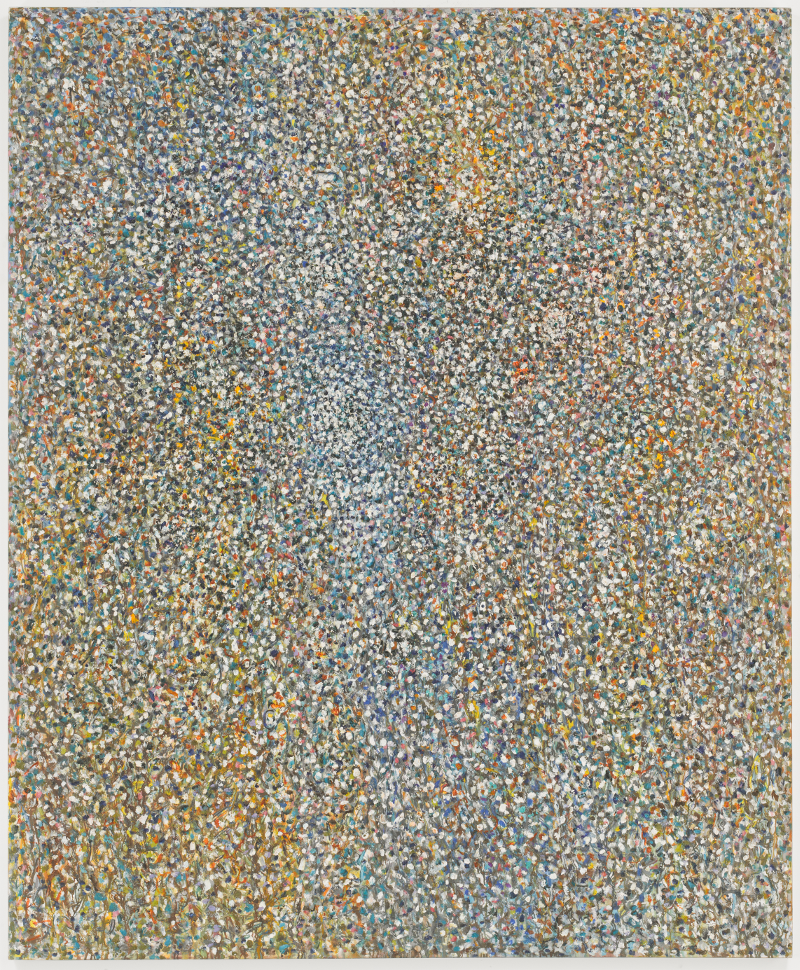

Meditation on the Drifting Stars, 1962-63, oil on linen by Richard Pousette-Dart. © 2017 Estate of Richard Pousette-Dart / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photograph by Kerry Ryan McFate, courtesy of Pace Gallery

Meditation on the Drifting Stars, 1962-63, oil on linen by Richard Pousette-Dart. © 2017 Estate of Richard Pousette-Dart / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photograph by Kerry Ryan McFate, courtesy of Pace Gallery“The Living Edge of Awareness”

Richard Pousette-Dart’s Poetry of Light and Space

“The true artist continually calculates the nature of the universe.

He makes visible what cannot be seen.”1

“[M]y canvases are just this, a final experience of white on white, having traveled thru and thru [sic], like an area of ground where much dancing has occurred.”2

Deeply sensitive to the power of the creative act, Richard Pousette-Dart constructed his own universes through each object he produced. His works on paper, his canvases, his photographs and his writings each radiate with the energy—physical, psychic, atomic—he experienced in the world around him. In the mind and hands of Pousette-Dart art functions as an analogue for life and for the macrocosm it inhabits.

The present exhibition, Richard Pousette-Dart: Painting/Light/Space, focuses attention on the artist’s activity during the period of the 1960s and early 1970s, positioning this moment as a hinge between his precocious beginnings as one of the youngest members of the New York School and his later career as a visionary elder statesman, sharing his work and his philosophy through his exhibitions, writings, and teaching with numerous emerging practitioners, including his students, such as artists Christopher Wool and Ai Weiwei.

Developed during the “space age,” the paintings and drawings gathered together here both anticipate and encompass the era during which science and technology would vault human beings into the cosmic arena—which Pousette-Dart had already envisioned in his art. His testaments to this vast zone, demarcated perhaps by the sorts of liminal boundaries he intuited in his own work, are not illustrations but highly sensitive recordings that convey the pulsating forces flowing around him. The vibrant surfaces of Pousette-Dart’s compositions, in which light’s potency and volume clarify themselves, reflect the artist’s early affiliation with Abstract Expressionism and simultaneously point the way to new practices dedicated to capturing and suggesting illumination. It is these vibrant abstractions we celebrate here at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, works that invite exuberant engagement and mindful contemplation, conveying, as Pousette-Dart might have it: “not the hard edge nor the soft edge/ but the living edge of awareness/the trembling edge of creation.”3

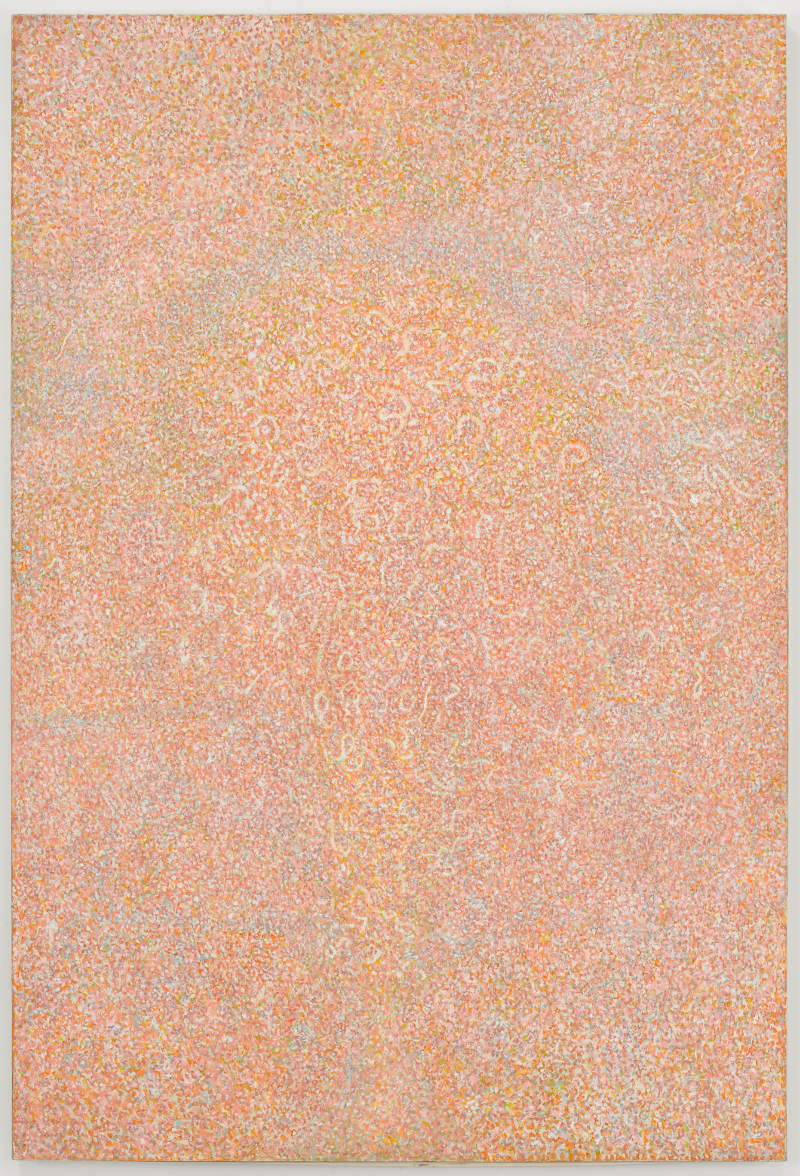

Presence, Amaranth Garden #1, 1974, oil on linen by Richard Pousette-Dart. © 2017 Estate of Richard Pousette-Dart / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photograph by Kerry Ryan McFate, courtesy of Pace Gallery

Presence, Amaranth Garden #1, 1974, oil on linen by Richard Pousette-Dart. © 2017 Estate of Richard Pousette-Dart / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photograph by Kerry Ryan McFate, courtesy of Pace GalleryIn the Studio

Richard Pousette-Dart and the studio in which he worked for decades recall for me a vivid set of childhood memories, intertwined with those of summer days outdoors and daylong adventures with my two friends who lived down the road from my grandparents’ stone carriage house.

The home was an open-door, flowing environment; one blending indoors and outdoors. There was a screen door by the oak tree on the side of the house and the sounds of the brook at night came through open windows. As children, we were always in and out, as the spirit of the home and property lent itself to a freedom of youthful exploration and activity.

After hours of hiking, biking and sports, we would take a break from our hijinks to return to the house. We’d run up the stairway and into my grandfather’s studio, knowing that we would find Richard painting. We also knew he’d at once set out art materials for us: cardboard, string, Styrofoam, wood, nails, paint, brushes, and glue.

Amidst the large canvases set on easels, the floor, and leaning against chairs and racks, Richard would turn up the music and set us to work. As we sprawled upon the multicolored wooden floor making a cardboard banjo, a painting, or a wooden block sculpture, Richard returned to his canvas. Calmly, steadily—his concentration uninterrupted—he resumed building the surface of a painting: dabbing applications of paint to transform singular marks into expansive sheets of color and texture, a process he used making the paintings in the current exhibition, Richard Pousette-Dart: Painting/Light/Space.

The studio wasn’t precious. It wasn’t off limits. It is where good things happened; where fine art was made amidst children experiencing art for the first time. It was filled with artworks and art materials, cameras and model airplanes, slingshots and cabinets filled with collections, all within a house on a plot of land that was important to my grandfather and to his art. The paintings in the current exhibition are evocative of those summer days in the studio and the woods surrounding it.

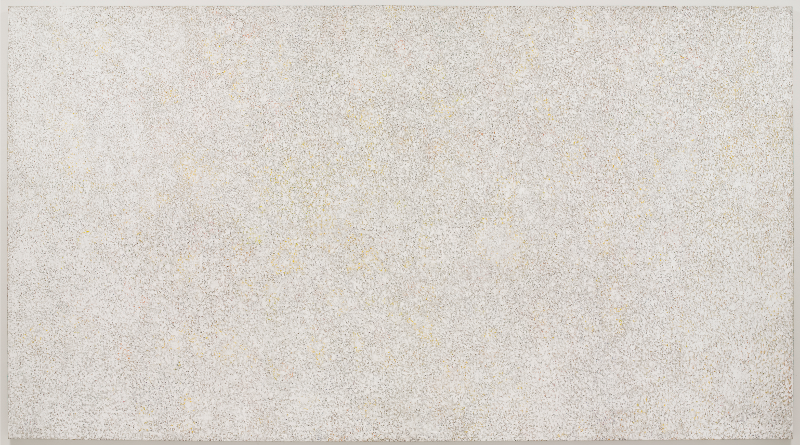

White Silence, 1974, acrylic on linen, by Richard Pousette-Dart. © 2017 Estate of Richard Pousette-Dart / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photograph by Kerry Ryan McFate, courtesy of Pace Gallery

White Silence, 1974, acrylic on linen, by Richard Pousette-Dart. © 2017 Estate of Richard Pousette-Dart / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photograph by Kerry Ryan McFate, courtesy of Pace GalleryThe Pleasure of Non-associative Seeing

In 1974, the Whitney Museum mounted its second exhibition devoted to Richard Pousette Dart, following an earlier retrospective by about ten years. It was a show that marked a definite shift in his painting from clearly defined symbolic shapes to an emphasis on disembodied light.Through the artist’s all-over application of small touches of color a shimmering luminosity glowed from the canvases on the museum walls. For the present exhibition, the Bowdoin College Museum of Art has wisely chosen to focus on that same period of Pousette Dart’s work, 1961 to 1974. (One earlier work, Shadow of the Unknown Bird, 1958, is included as a prelude.) Because much of the philosophy that underlay his art from the outset reached its fullest realization in this body of work, the current selection offers an ideal entry point to gain insight into his core motivations.

“I want to keep a balance just on the edge of awareness, the narrow rim between the conscious and sub-conscious, a balance between expanding and contracting, between silence and sound.”4 His emphasis was on the process of seeing, rather than on directing the viewer to an external reference. His aim was to create objects of meditation, and through them to engender a consciousness of interconnectedness and a perception of over-all unity.

Among the means he spoke of using to achieve a “balance on the edge of awareness” were tuning, livingness of edges, density, and duration. Tuning was the process used to make all parts of the canvas vibrate in harmony; this involved adding small touches of contrasting color that would interact with a pulsating effect. Livingness of edges refers to the ambiguity of edge and the absence of finite shape; flurries of small touches of paint, rather than firm lines, define the transition from one area to another and produce a hovering quality. Density derives from a layering of points of color to produce a multiplicity of sensations, requiring continual retinal adaptation. Refracted light from the many irregularities of the textured paint joins with the shifting highlights and after-images emanating from the painted surface to intensify the over-all vibrancy. Since an exact replica cannot be held in the mind, attention must constantly return to the actual work. This is what is meant by duration—the painting does not reveal itself all at once but must be perceived over time.

Pousette Dart spoke often of an “unending chain of being which he sought to express through form that was “forever resolving and dissolving, growing and decaying, being born and dying, becoming and disappearing, form perceived through millions of points of light.”5

Applying paint with the tip of his brush, he would make thousands of such points; points that might be understood as equivalent to the particles that constitute light. Watching him at his easel one had the sense that he was transmitting energy from the surrounding space, making it manifest as light, engendered by the color interactions on his canvas.

For him this constituted “presence,” a sensation of the ineffable that stirs within the painting. Meditating on the light emanating from these surfaces, one is compelled to shift from an analytic linear mode of consciousness to a different level of awareness, a sensory mode that is experiential and intuitive.

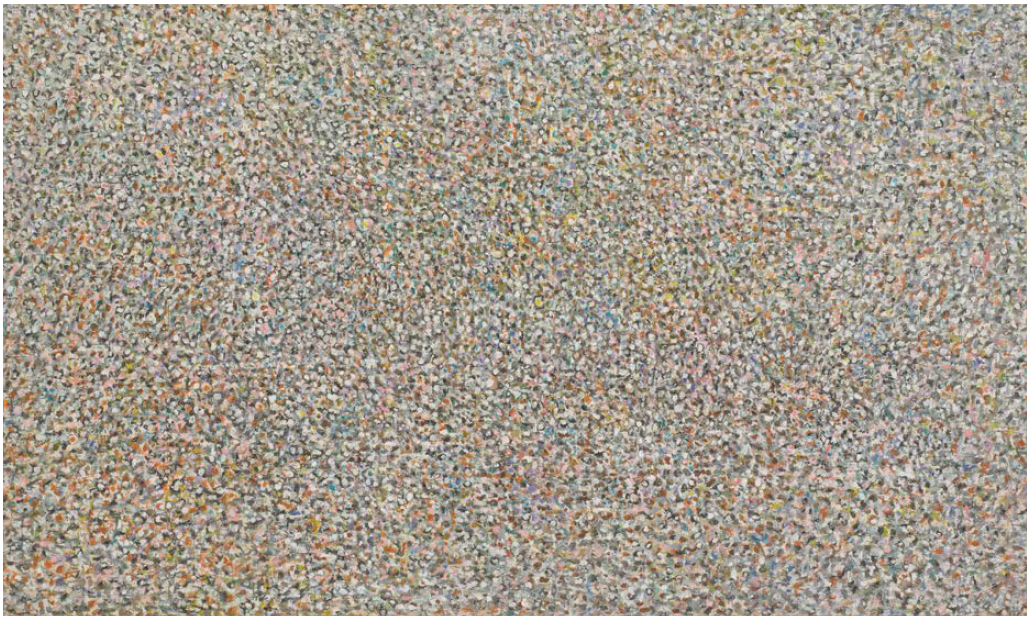

Magnetic Space, 1961, oil on linen by Richard Pousette-Dart. © 2017 Estate of Richard Pousette-Dart / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photograph by Kerry Ryan McFate, courtesy of Pace Gallery

Magnetic Space, 1961, oil on linen by Richard Pousette-Dart. © 2017 Estate of Richard Pousette-Dart / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photograph by Kerry Ryan McFate, courtesy of Pace GalleryGetting to the Point

The delicate harmonies of Richard Pousette-Dart’s paintings and drawings from the 1960s and 1970s are achieved through the masterful interplay of particulars and wholes. Akin to how art historian Erwin Panofsky described experiencing the resplendent naturalistic panel paintings of early Netherlandish master Jan van Eyck, the eye of the viewer is invited to oscillate between a macroscopic, overall conception of a works and its microscopic particulars. Pousette-Dart’s elemental components are multitudinous touches of paint and minute lines of ink, placed and layered and combined until paintings and drawings resonate as shimmering, unified statements. Celebrations of light, color and form, these works utilize abstraction to offer multiple vantages on the idea of space, including expanding and converging recessional depth, and sweeping cross-sections of seeming infinitude.

Pousette-Dart’s technical approach to painting from the second half of his career has often been tied erroneously to Pointillism, the Neo-impressionistic practice of creating imagery through dots, famously championed by Georges Seurat during the late 1880s in France. But where Pointillism is firmly rooted in rigorous scientific studies and systems of applied color, Pousette-Dart’s technique is, however, entirely intuitive. If we are to search for an outside, guiding model for his later approach to painting, we may be surprised to discover a lesser-known facet of his overall artistic practice: photography.

Pousette-Dart was deeply engaged with photography throughout his life. He exhibited his fine-art portraits and nature studies at the Betty Parsons Gallery in 1948, and in 1953 received awards from Photography magazine. As a young man setting out to pursue a career as a professional artist, he supported himself as a secretary in the Manhattan studio of Lynn T. Morgan, an art director, painter, and print-maker whose photographic studio specialized in retouching black-and-white and color photographs. For the young Richard Pousette-Dart this appointment was transformational. Not only did it offer training in detailed hand-manipulation of photographic prints and negatives, more profoundly it provided the opportunity to scrutinize the enlarged granular structure of film, revealing to the painter that “all form is made up of so many points of light and that everything has a molecular structure. Photography was how I got to the point…I’m concerned with form and the nature of light, and I find that I can achieve variations in form through many touches of the brush in a way that I can’t with a single stroke of the brush.”6

Hieroglyph Number 7 (Heiroglyph of Light), 1968-69, oil on linen by Richard Pousette-Dart. © 2017 Estate of Richard Pousette-Dart / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photograph by Kerry Ryan McFate, courtesy of Pace Gallery

Hieroglyph Number 7 (Heiroglyph of Light), 1968-69, oil on linen by Richard Pousette-Dart. © 2017 Estate of Richard Pousette-Dart / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photograph by Kerry Ryan McFate, courtesy of Pace GalleryPousette-Dart as Mentor and Maverick

For an artist who did not attend an art school but absorbed lessons from his father, a painter and art historian, and his mother, a poet, Richard Pousette-Dart developed an unlikely passion for academic teaching. In many classrooms he was a mentor and a maverick, who challenged students to let practical experience guide them.7 “The best way to talk about art is to work. The best way to study art is to work. The best way to think about art is to work. Art is to work hard and one day it may become art and you may discover the artist that you are.”8 The creative process, for him, finds its fulfillment in two kinds of growth. “My paintings grow as flowers in a garden grow; together, yet in many different directions and ways.” The formation of paintings mirrors the adventure of increasing self-awareness and realization. Art is nurturing—this was the credo of Pousette-Dart as a painter and it predisposed him to teach as well.

In a teaching statement, Pousette-Dart vehemently refuses to commit to a lesson plan. Instead, he insists that for creativity “mandatory skills are destructive to the inspiration of true, original, creative thinking and feeling.” The teacher sets a positive example by living an unconditional commitment to art making. “We can only teach what we have the courage to be ourselves.”9 The paintings not only express, they constitute that being and serve, according to an undated note in the archives, as “presences or grounds wher[e]on my experience may mingle with others.” This teaching philosophy is ingrained in the paintings in the exhibition. The works emerge in the viewers’ eyes out of myriad dabs of paint. Whether densely built up or effortlessly floating, sparkling or receding, marks of the brush carry a transient energy as they appear in and fade out of view, seemingly on their own accord.

Pousette-Dart located the meaning of his works in “some strange inner kernel…it is this dimensionless particle which lives, breathes, and means.” His paintings on view can be understood as visual experiments that trace this “kernel” and in so doing explore the viability of non-referential visual communication. In hindsight, Pousette-Dart’s painting practice of the 1960s and early 1970s seems in sync with advanced developments in arts and sciences of the time. He participated in a paradigm shift in 1960s art “from the individual creative act to a description, investigation, and development of communication systems and visual codes,” to use media theorist Boris Groys’s words. Like other artists of the period, Pousette-Dart painted within very clearly set parameters that he interpreted in various ways, thereby provoking the viewer “to imagine the generative code, to imagine all the variations that can be generated by the code.”10 Concurrently with his efforts, scientists and system theorists developed the concept of “autopoietic” systems, describing such a system’s ability to maintain itself in terms that one might apply to Pousette-Dart’s painting process as well.

One of the most resilient motifs in Pousette-Dart’s paintings, as they dissolve from totemic, semantically organized symbols into shimmering surfaces of dabs of paint, is the “hieroglyph.” This pictogram, which remains undecipherable to the viewer, draws attention to the process of coding, the structural transformation that generates bits of information. With scholar Meredith Hoy, who studies the rise of digital aesthetics, one could describe any of his paintings of the 1960s and early 1970s “as aesthetically digital, that is, it renders its visual data as a formal array of discrete elements that correlate to a definite informatics quantity.” Acknowledging the differences between “digital and analog modalities” in art one might trace its particular “type of meaning” by identifying the work as part of a digital tradition that precedes the application of computer processing.11 Pousette-Dart’s teaching philosophy and his innovative pictorial language reveal an artist with a singular vision, sure-footed intuition, an open mind, and generous spirit.

About the Artist

Richard Pousette-Dart (June 8, 1916—October 25, 1992) enjoyed early success as a member of the New York School. The son of the painter and writer Nathaniel Pousette-Dart and the poet Flora Louise Dart, Richard studied only briefly at Bard College before making a name for himself in New York art circles. He became widely known for exhibiting one of the first mural-sized canvases of the New York School, Symphony Number 1, in 1941. While in his early work Pousette-Dart explored totemic and symbolic forms that were derived from non-Western and Medieval art, he later turned towards geometric shapes and covered canvases with short brushstrokes of pulsating color. Pousette-Dart’s work has been featured in solo exhibitions at the Whitney Museum of American Art (1963, 1974), the Indianapolis Museum of Art (1990—92), the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1997—98), the Museum of Fine Art, Houston (2001—02), the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (2006—07) and the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice (2007—08), among others. He taught at the Art Students League, the New York School for Social Research, Columbia University, and Sarah Lawrence College.

Acknowledgments

This exhibition grew out of the life-long friendship between Evelyn Pousette-Dart and Esta Kramer, who were introduced to each other by their mutual friend Martica Sawin more than 50 years ago. The Pousette-Dart family made the exhibition possible, with exceedingly generous loans from the artist’s estate, represented by Chris Pousette-Dart and aided by Joanna and Jonathan Pousette-Dart. Charles Duncan, Executive Director, The Richard Pousette-Dart Foundation, was an insightful and experienced collaborator in all phases of the preparation of this exhibition. He was supported by Charlotte Nicholson, Archivist of the Foundation. Douglas Pace, President, Pace Gallery and his team provided logistical support. Sharon Corwin, Carolyn Muzzy Director and Chief Curator, and our colleagues at the Colby College Museum of Art kindly lent a recently acquired masterpiece. We are profoundly grateful to all of these partners. Financial support for the exhibition and this publication was provided by the Becker Fund for the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, the Stevens L. Frost Endowment Fund, the Elizabeth B. G. Hamlin Fund, and the Roy A. Hunt Foundation.

Notes

- Richard Pousette-Dart, describing a thought recorded about 1950 in a conversation with Martica Sawin, about 1974; in Martica Sawin, “Richard Pousette-Dart,” in Richard Pousette-Dart: The Centennial (New York: Pace, 2016), 7

- Richard Pousette-Dart, SOURCE NEEDED. Quoted in Alex Bacon, “Richard Pousette-Dart’s Luminous Geometry,” in Richard Pousette-Dart (New York: Pace, 2014), 5.

- Richard Pousette-Dart, Notebook B 152, 1973—74. Quoted by Lowery Sims, “Ciphering and Deciphering: The Art and Writings of Richard Pousette-Dart,” in Richard Pousette-Dart (1916—1992), edited by Lowery Stokes Sims and Stephen Polcari (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1997), 17.

- conversation with the author, September 1964.

- Pousette Dart studio notebook B196, 1976.

- Duncan, Charles H. Absence/Presence: Richard Pousette-Dart as Photographer. Foreward by Anna Tobin D’Ambrosio. Acknowledgments by Mary E. Murray. Utica, N.Y.: Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute, 2014. p. 13

- Pousette-Dart held teaching appointments at New School for Social Research (1959—61) and the School of Visual Arts (1964), New York, Bard College (1965), Columbia University (1968 — 69), and Sara Lawrence College (1970—74). He received an honorary degree from Bard College, where he had enrolled in 1936 for just a few months.

- Convocation lecture, Minneapolis School of Art on November 2, 1966, manuscript at the Pousette-Dart Foundation archives, Suffern, NY. Emphasis by the artist.

- “To the Curriculum Committee, From Richard Pousette-Dart, March 14, 1972,” manuscript in the Archive of the Richard Pousette-Dart Foundation.

- Boris Groys, The Mimesis of Thinking, in Open Systems: Rethinking Art c. 1970, ed. Donna De Salvo, London: Tate Publishing, 2005, pp. 51—64, quote pp. 52—53.

- Meredith Hoy, From Point to Pixel: A Genealogy of Digital Aesthetics, Hanover, NH: Dartmouth College Press, 2017, pp. 2 and 6